We all have passions and dreams, which our parents might not always agree with. In a stereotypical Asian family, artistic and creative dreams tend to be frowned upon, and we might have second thoughts about chasing them.

Writing is something I love. Seven year old me rushed home after school and wrote fictional adventure stories in my bedroom, and loved writing essays for English classes. These days after work, I write for this blog and work on my first book. But for as long as I can remember, my Chinese-Malaysian parents have never been keen on me spending time writing.

One can say Asian parents are harsh and narrow-minded when they rather their kids pursue one dream over the other. Others might say Asian parents are simply looking out for us.

If it doesn’t earn bring in a decent paycheck, to some stereotypical parents that creative dream might not be worth chasing as it “isn’t practical” in the long term. Material success and making strides in one’s career is the pride and face of countless Asian families. To achieve this, it’s common sense to have a reputable job and dream that pays the bills and hit the shops. Arguably, professions in the arts involve evaluation while careers in fields like medicine and engineering have a higher potential of shielding one from (cultural and non-cultural) biases by employers and clients.

In the months leading up to graduating from university with a Bachelor of Arts, my mum kept hovering over my shoulder. “Apply for jobs at the big companies like the Tax Office. Bureau of Statistics. Commonwealth Bank. More money,” she said each time she saw me sitting in front of my laptop in my room after classes. I would be looking up and chasing publication after publication after yet another publication in hope they’d take a look at articles I’ve written.

Honouring one’s parents and supporting them in their later days is a virtue in Asian cultures. Creative endeavours don’t promise this, at times not even food on the table tomorrow. Confucianism has long been a fundamental part of Chinese society dating back to the Han dynasty and filial piety is one of the philosophy’s values. Today Confucianism is still highly esteemed and in China a percentage of one’s wages might be deposited into parents’ bank accounts. As a writer or reporter for a magazine, one might work odd hours when an assignment comes up and get paid as and when one gets published. As a painter or musician, not all exhibits and performances promise returns.

“Don’t anyhow spend your money. Buy me a house next time,” as my mum likes to say to me. It’s already hard enough to buy a place for yourself in Australia unless you make millions.

Creative dreams encourage us to speak out and express ourselves, whereas hierarchical Asian family structures encourage otherwise. Elders are assumed to be correct in Asian cultures. Going against their word is seen as disrespectful; tradition and superstition, the tried and tested, are regarded as common sense. The pathways of business, medicine and law have time and time again made numerous cities in the Asia Pacific region the progressive cities they are today.

In Asian cultures there is also the mentality that doing over and over what has always worked brings success. As such, some “don’t get” creative passions where one needs to be spontaneous to inspire progress.

Having been brought up in a culture of routine, it’s no surprise some Asians don’t know how to go after their creative dreams, and hesitate and end up fitting the passive stereotype. It can be hard not listening to our parents: we feel guilty if we don’t because our parents may have sacrificed much for us, for example moving to the Western world to give us a better life or working three jobs at a time. We feel like we owe them and feel the need to be who they want us to be, like that hardworking student or dedicated career climber.

Many Asian Australians continue to fit such stereotypes. Research in 2013 shows students of east and south-east Asian background are 30 times more likely to make the Maths Extension 2 HSC honour roll than their Anglo counterparts, and dominate 10 out of 13 of the most popular honour roll subjects. Only recently over the last decade are Asian Australians pursuing careers in the arts and media more despite bamboo-ceiling resistance.

Time and time again, we might feel our stereotypical Asian parents “are right” about our creative dreams. It’s common for creatives to work a job on the side to pay the bills as your creative work, be it painting or writing or photography, is often hard to sustain a living.

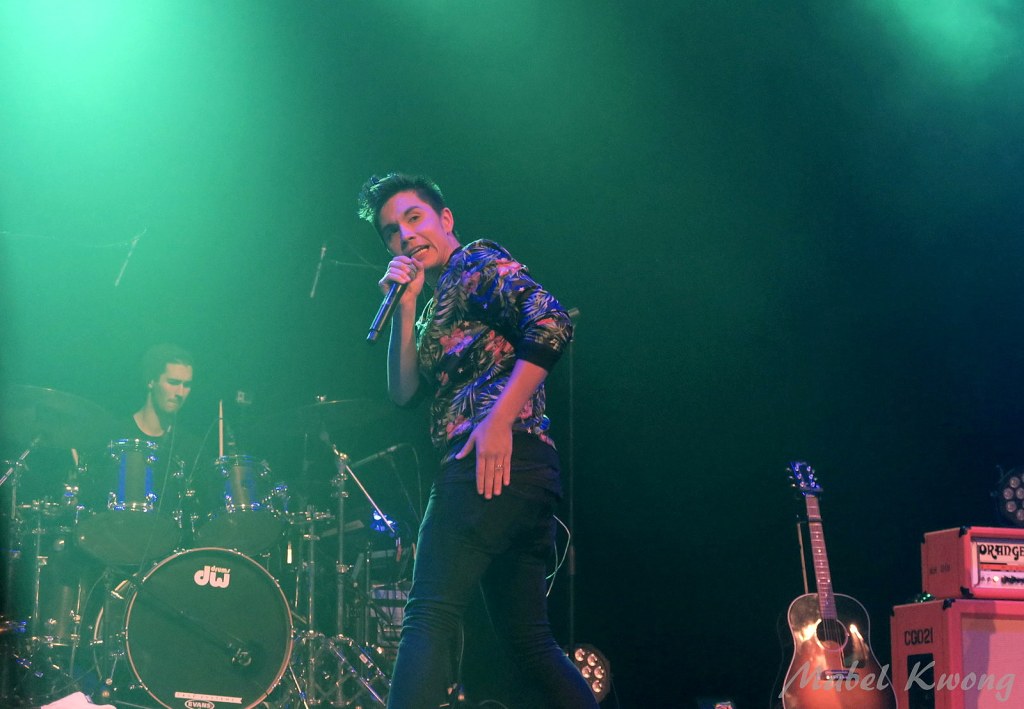

There’s no reason why we can’t pursue our creative dreams under the disguise of hobby. No reason why we can’t create opportunities out of our down time. As singer Sam Tsui said on chasing your dreams:

“You just have to trust that if you have something unique….You can just go ahead and do it. [If] you have something to say, it’ll stick somewhere.”

Sometimes going after our creative dreams entails keeping to ourselves and not shouting it from the roof tops. Having always grown up with the typical Asian mindset, perhaps we have to learn to be a bit selfish and put our individual selves first in order to keep doing that creative thing that we love. Writing is something I generally keep to myself these days and don’t talk about it unless someone is genuinely curious about my work.

Coming from a typical Asian family, chasing our creative dreams involves waiting and creating our own chances as we live the Asian stereotype and non-stereotype. Who says we can’t experience the best opportunities from both worlds, one bit at a time?

Certainly not all Asian parents disapprove of all creative ventures. Countless Asian parents are willing to pay for piano and violin lessons for their kids, and in turn take pride in watching them perform the keys and bring home musical accolades and certificates at the very least. At university, I told my parents no more piano lessons, no piano diploma for me. Though I loved these lessons, I explained to them I wanted more time to practice differentiation and integration maths formulas…and silently told myself, more time for writing too. As producer Kurt Hugo Schneider said on committing and working hard at your craft:

“If you want to be the best at something, you have to do it to the exclusion of everything else.”

What we do makes who we are, and who we are makes what we do. Just as cultural stereotypes can hold us back from going after our dreams, they can also be the very traits that help us go after them.

When you have no expectations, every milestone is an achievement. When you make the most of the pieces in your hands, who knows where you can go, no matter where you come from.

Do you and your parents agree on your dreams?

Share your thoughts. Join the discussion